Description

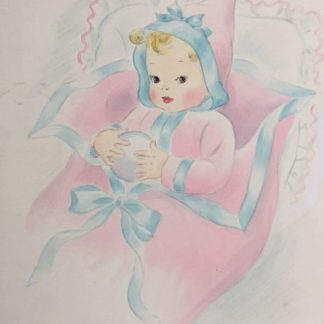

11 1/2″ x 14 1/2″ full sheet, image 8″ x 9″, watercolor on heavy paper. Very pale early pastel. Buyer pays for shipping.

There are three other paintings in this series posted a while ago. Please do a search for “Nursery.” From the 40’s. These are attributed to Maud Fangel. They are very vintage/delicate looking. DAC reproduced her work and these resemble those reproduced; however, the exact illustrations were not found.

Biography from the Archives of askART

In the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s — if you saw a sketch or portrait of a child on the cover of Ladies Home Journal or Woman’s Home Companion, or inside the magazines’ advertising, say, Colgate’s Talc Powder, Cream of Wheat, or Squibb’s Cod Liver Oil, you were probably seeing the work of Maud Tausey Fangel. For a good part of the first half of the twentieth century, Ms. Fangel was the children’s artist in our country — her illustrations of ruddy-cheeked, doe-eyed, curly-locked children were everywhere. They set the standard for their day and made Ms. Fangel a kind of celebrity — the subject of frequent feature articles and a much in demand children’s portrait painter, who was commissioned to do pictures of the Dionne Quintuplets and the children of Chiang Kai Shek.

Maud Tausey was born on January 1st, 1881, the daughter of a Professor of Divinity at Tufts College, later Tufts University, in the Boston area. She began drawing in earnest when she was a teeanger and studied at Boston’s School of Fine Arts before coming to New York City on a scholarship to Cooper Union to continue her studies. Soon she was presenting her portfolio to the art director of Good Housekeeping, Guy Fangel, who gave her her first commercial assignments and later proposed marriage to her. Their son, Lloyd, began Ms. Fangel’s fascination with drawing babies — she did more than 1500 pictures of him before he was three — and later she would immortalize his face as the boy on the Cracker Jack box.

Many of Ms. Fangel’s pictures were done in pastels, which allowed her to capture the movements of her young subjects in swift, impressionistic strokes. Most of Ms. Fangel’s models were children from poor families, from orphanages, and settlement houses. Unaware of this, one newspaper referred to these children as “glamore babies.” But Ms. Fangel understood the youngsters who sat and wiggled and dozed in the high chair for her a little more deeply than the correspondent: “I have a strange, persistent feeling that babies have a consciousness that we do not possess,” she wrote. “They seem not yet to have lost an intelligence brought with them from another world. They are still wrapped in the mystery of their source.”

When she died at the age of 87, Ms. Fangel was working on a book about a day in the life of an African-American child. But in the racially divided America of the1950s, every publisher she submitted the project to turned it down, unwilling to move forward on an idea that was years ahead of its time. But that was always true of Maud Tausey Fangel. She and the children she painted were waiting for the future to catch up.